libros abril

extremely loud & incredibly close

by jonathan safran foer

i'm loving this book right now. actually, i'm having a hard time figuring out how to write about it, it seems kindof impossible to just describe it. the basic jist of the book: it's about a 9-year-old boy who's dad died in the world trade center on september 11. most of the book revolves around how he finds a key of his dads & goes on a journey around new york trying to find the lock that it opens. the book has gotten reviews calling it "the first great novel about september 11." personally i love this guys funky style of telling a story (he also wrote the book "everything is illuminated"), but more than that i just think he delves into the nastier side of life in a way that is truthful but also hopeful. here's a random sampling (the whole book is told from the perspective of 9-year-old oskar.)...

'an ambulance drove down the street between us, & i imagined who it was carrying, & what had happened to him. did he break an ankle attempting a hard trick on his skateboard? or maybe he was dying from third-degree burns on ninety percent of his body? was there any chance that i knew him? did anyone see the ambulance & wonder if it was me inside?

what about a device that knew everyone you knew? so when an ambulance went down the street, a big sign on the roof could flash

on the road by jack kerouac

weeeellll... i read 'jane eyre' for the first time when i was about 11. but i read 'the catcher in the rye' for the first time when i was about 24. which is to say, my obsession with british books seems to have kept me from some of the good 'ol american classics. so, i'm trying to catch up now. considering the importance of travel in my life & philosophy, it's kindof insane that i'm only now reading 'on the road.'

i'm getting ready to move to seattle for the summer. then... chicago? so i thought now would be a good time to read some kerouac & remind myself

that i live the way i do on purpose, & not just because i can't bring myself to stay still.

that i live the way i do on purpose, & not just because i can't bring myself to stay still.'what is that feeling when you're driving away from people & they recede on the plain till you see their specks dispersing? --it's the too-huge world vaulting us, & it's good-by. but we lean forward to the next crazy venture beneath the skies.'

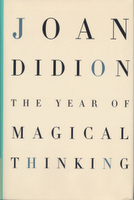

the year of magical thinking

by joan didion

'life changes fast.

life changes in the instant.

(the ordinary instant.)

you sit down to dinner & life as you know it ends.

the question of self-pity.'

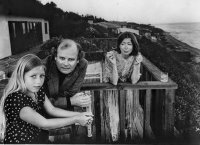

joan didion (who is apparantly one of 'america's iconic writers,' although i'll be honest & tell you i'd never heard of her 'til i randomly picked this book up off a shelf in borders one day) started writing this book less than a year after her husband died. in late december 2003, she & her husband john gregory dunne came home from visiting their only daughter in the hospital where she had been, in a coma, for the last several days. they were sitting down to have dinner when john had a heart attack & died on the spot. her daughter survived, only to collapse 2 months later at LAX & be rushed to the hospital for brain surgery.

the next year is what joan didion calls 'the year of magical thinking,' in the middle of which she sits down to write with brutal honesty about grief, life, marriage, death & 'the shallowness of sanity.' this book is crazy good. i've read alot of stuff about grief, & i personally think this one is right up there with 'a grief observed' by c. s. lewis.

'grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it. we anticipate (we know) that someone close to us could die, but we do not look beyond the few days or weeks that immediately follow such an imagined death. we misconstrue the nature of even those few days or weeks. we might expect if the death is sudden to feel shock. we do not expect this shock to be obliterative, dislocating to both body & mind. we might expect that we will be prostrate, inconsolable, crazy with loss. we do not expect to be literally crazy, cool customers who believe that their husband is about to return & need his shoes. in the version of grief we imagine, the model will be "healing." a certain forward movement will prevail. the worst days will be the earliest days. we imagine that the moment to most severely test us will be the funeral, after which this hypothetical healing will take place. when we anticipate the funeral we wonder about failing to "get through it," rise to the occasion, exhibit the "strength" that invariably gets mentioned as the correct response to death. we anticipate needing to steel ourselves for the moment: will i be able to greet people, will i be able to leave the scene, will i be able even to get dressed that day? we have no way of knowing that this will not be the issue. we have no way of knowing that the funeral itself will be anodyne, a kind of narcotic regression in which we are wrapped in the care of others & the gravity & meaning of the occasion. nor can we know ahead of the fact (& here lies the heart of the difference between grief as we imagine it & grief as it is) the unending absence that follows, the void, the very opposite of meaning, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaninglessness itself.'